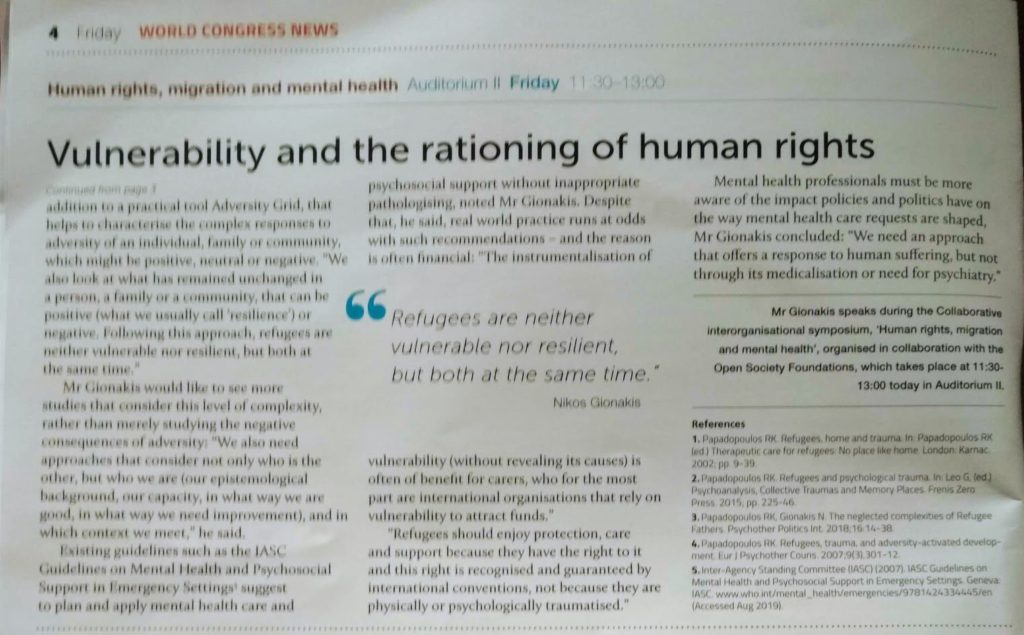

Δημοσιεύθηκε στο newsletter του Παγκόσμιου Συνεδρίου Ψυχιατρικής που διεξήχθη στην Λισαβόνα μεταξύ 21-24 Αυγούστου 2019.

Vulnerability and the rationing of human rights

Mental health professionals must be more nuanced in their approaches to refugees, according to Nikos Gionakis, head of the Babel Day Centre – the only mental health unit in Greece for migrants and refugees. Mr Gionakis will be presenting at this morning’s session organised in collaboration with the Open Society Foundations.

Greece has taken in huge numbers of refugees, many of whom are stuck in camps on the islands. “They live in inhumane conditions,” Mr Gionakis told World Congress News. For example, he explained, in the last days of July a reception and identification centre on the island of Lesvos with a capacity of 3,000 reached a population of 7,000 – including many minors.

The Babel Day Centre, which has operated since 2007, hosts a wealth of experience in dealing with refugees who present with severe psychosocial problems and established mental disorders. It also processes requests for support – through training, consultation and supervision – submitted by colleagues working on the front line. “There are many challenges,” said Mr Gionakis. “These are humanitarian crisis settings, and we are asked to provide mental health services in unhealthy and pathologizing environments.”

Today, however, one of the most pressing issues has become ‘vulnerabilization’: “A person is only given access to their rights – whether human, asylum seeker or refugee rights – if they are classed as vulnerable,” explained Mr Gionakis. In other words, many refugees can receive basic help only if they are labelled as vulnerable.

“To prioritize the examination of a request for asylum, for a family to be re-unified (and without waiting too long), to be free to move from the islands to the mainland, to move from a camp to an apartment, to continue staying in an apartment and not be evicted, one needs to be vulnerable.”

Crucially, added Mr Gionakis, this system applies not only in Greece, but within the whole of the European Union.

The problem with this approach, he continued, is that vulnerability is defined within very rigid criteria. “One is either vulnerable or resilient. One consequence of this polarized logic is the equation ‘vulnerable = ok, resilient = dangerous’.”

He went on to cite the work of Professor Renos K Papadopoulos of the Centre for Trauma, Asylum and Refugees of the University of Essex, which extensively addresses this issue[#1].

Mr Gionakis also noted further incorrect assumptions abound about refugees: “Another stereotype that has appeared assumes that all refugees are traumatized in a way and have developed different mental disorders, the most common of which is PTSD.”

By casting a person in this particular light, he explained, mental health professionals are in effect ignoring the complexities of refugee experiences both past and present. “The history of a person is reduced to the history of his or her trauma,” he said. “And such a practice has a serious impact on either the way people ask for help (e.g, referral pathways), or present their request for help.

“We neglect the fact that refugees have their own plans, expectations, dreams (just like anyone) and that they use reality to achieve their goals, first of which is to survive. Refugees may use psychiatric symptoms, not to ask for help to cure them, but to get access to basic provisions and fundamental human rights.

“Most concerning is that half of those who get a statement regarding their mental health interrupt the relationship with the service despite the need to continue psychiatric or psychological treatment.”

Indeed, the effects of this contradictory system were laid bare when the Greek government began to evict recognised refugees from accommodation they had already been assigned, with the only exceptions to this rule those facing particular challenges or classed as vulnerable: “The Babel Day Centre saw an increase in requests by refugees living in the apartments to be examined for mental health issues, in part so that they should continue staying in the apartments,” explained Mr Gionakis.

During his presentation, Mr Gionakis will discuss a theoretical approach, developed by Professor Papadopoulos and adopted in his centre, that could counteract this effect. The Adversity Activated Development [#2] postulates that there are multiple consequences of being exposed to adversity, not just the kind that can lead to the appearance of pathological manifestations: “There are new positive features, characteristics and qualities that someone gains because of their exposure to adversity.”

The Adversity Activated Development approach calls for a more nuanced understanding of refugees, and Mr Gionakis will outline this in addition to a practical tool Adversity Grid, that helps to characterize the complex responses to adversity of an individual, a family or a community, which might be positive, neutral or negative. “We also look at what has remained unchanged in a person, a family or a community, that can be positive (what we usually call ‘resilience’) or negative. Following this approach, refugees are neither vulnerable nor resilient but both, at the same time.”

Mr Gionakis would like to see more studies that consider this level of complexity, rather than merely studying the negative consequences of adversity: “We also need approaches that consider not only who is the other, but who we are (our epistemological background, our capacity, in what way we are good, in what way we need improvement), and in which context we meet,” he said.

Existing guidelines such as the IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings [#3] suggest to plan and apply mental health care and psychosocial support without inappropriate pathologizing, noted Mr Gionakis. Despite that, he said, real world practice runs at odds with such recommendations – and the reason is often financial: “The instrumentalization of vulnerability (without revealing its causes) is often of benefit for carers, who for the most part are international organizations that rely on vulnerability to attract funds”.

“Refugees should enjoy protection, care and support because they have the right to it and this right is recognized and guaranteed by international conventions, not because they are physically or psychologically traumatized.”

Mental health professionals must be more aware of the impact policies and politics have on the way mental health care requests are shaped, Mr Gionakis concluded: “We need an approach that offers a response to human suffering, but not through its medicalization or need for psychiatry.”

Mr Gionakis speaks during the Collaborative interorganizational symposium, ‘Human rights, migration and mental health’, organized in collaboration with the Open Society Foundations, which takes place at 11:30-13:00 today in Auditorium II.

References

- Papadopoulos RK. Refugees, home and trauma. In: Papadopoulos RK (ed.) Therapeutic care for refugees: No place like home. London: Karnac. 2002; pp. 9-39.

- Papadopoulos RK. Refugees and psychological trauma. In: Leo G, (ed.) Psychoanalysis, Collective Traumas and Memory Places. Frenis Zero Press. 2015; pp. 225-46.

- Papadopoulos RK, Gionakis N. The neglected complexities of Refugee Fathers. Psychother Politics Int. 2018;16:14-38.

- Papadopoulos RK. Refugees, trauma, and adversity-activated development. Eur J Psychother Couns. 2007;9(3),301-12.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2007). IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva: IASC. www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/9781424334445/en (Accessed Aug 2019).